Blog | The genius loci of design

Genius loci

The presiding god or spirit of a place

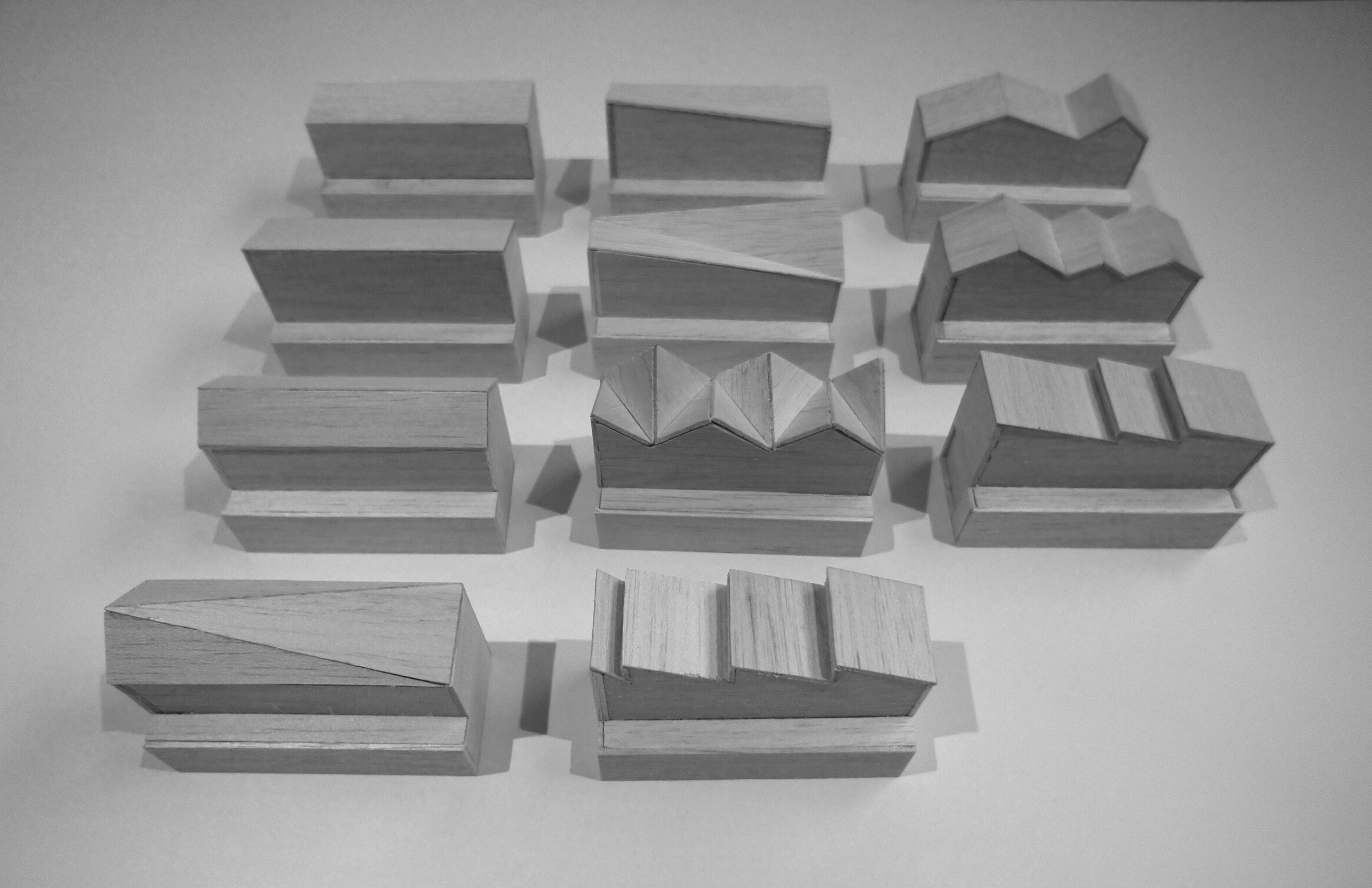

Does the spirit of Mihaly Slocombe’s design live in the pieces of yellow tracing paper that we fill with floorplans and diagrams? Or in the massing experiments we produce in SketchUp? Or in the presentation models we build from cardboard and balsa? Does it live in the resolution of a tricky construction detail? Or in the design feedback we receive from our clients? Or on site with a builder, thick pencils scratching details into a nearby timber stud?

For us, design happens in all of these places. It spans dozens or even hundreds of individual moments, strung out across a project from its very start to its very end. It involves many people, including our team, clients, builders, trades, consultants and (though it pains me to admit this) authorities. It relies on many media, including sketches, diagrams, models both digital and physical, CAD drawings and specifications.

These moments, people and media each hold a fragment of the genius loci of our design, but collectively they’re too numerous and too dispersed to represent its true spirit.

There is however a constant that binds them together: conversation.

Conversation is our genius loci. We communicate with words, our hands, careful sketches, hasty sketches, at length, in short, all the time. We talk at meeting tables, while standing over cardboard models, in front of computer screens. We agree, disagree, debate, argue, monologue, dialogue, rationalise, theorise and crack jokes.

Conversation forms a coherent narrative from cacophony. It liberates the people involved in our process to use any medium as a generator of design. It facilitates experimentation, design possibilities explored just to see what happens. It opens up our process to become more receptive of inspiration, at any point in a project. It removes the responsibility of authorship from the individual and smears it across the collective. It supercharges our ideas, testing and improving them through constant reflection and critique.

By nesting the genius loci of our design in conversation, we open ourselves to a broader understanding of what design is. Design does not mean sketch design, hoarded by Erica and I, it means all the work we do throughout the lifecycle of a project. We cherish the detail as much as we do the sweeping gesture. We think both big and little picture, deal in the currencies of ideas as well as craft.

The emergence of our eureka moments are unpredictable and delightful. Sometimes they appear in the masterplan, with a well laid out floor plan. Sometimes in sketch design, with the discovery of form. Or in detail design, with the refinement of materials. Once even, it arrived deep into documentation, while trying to resolve a stubborn flashing detail.

We shape our studio to this vision. We don’t have design teams and delivery teams, separate classes of people undertaking separate tasks. We have Renaissance architects. We all do it all.

We arrange our schedules so the team that starts a project finishes it. It helps us learn and it sows the seeds of shared authorship. It’s important to Erica and I that we all see ourselves in Mihaly Slocombe’s projects. We want the best for our work, for our team, for our studio. I’m pleased to say that I can’t recognise in any of our projects a singular hand, only a melting pot of combined influence.

I suppose this is a manifesto of sorts.

Writing it, I’m not just interested in how we design, but how we sustain a design culture. When we started Mihaly Slocombe, Erica and I produced every single piece of information that left our studio. Our creative process was almost entirely internal. But we’ve grown beyond just the two of us and we’re no longer solely responsible for making all the stuff.

We still provide the creative direction of our studio, but we’re not its genius loci. Our creativity now rests outside ourselves. With this metamorphosis comes a loss of control, but our hopes to protect the culture that makes us what we are remains.

What conditions will allow this culture to thrive?

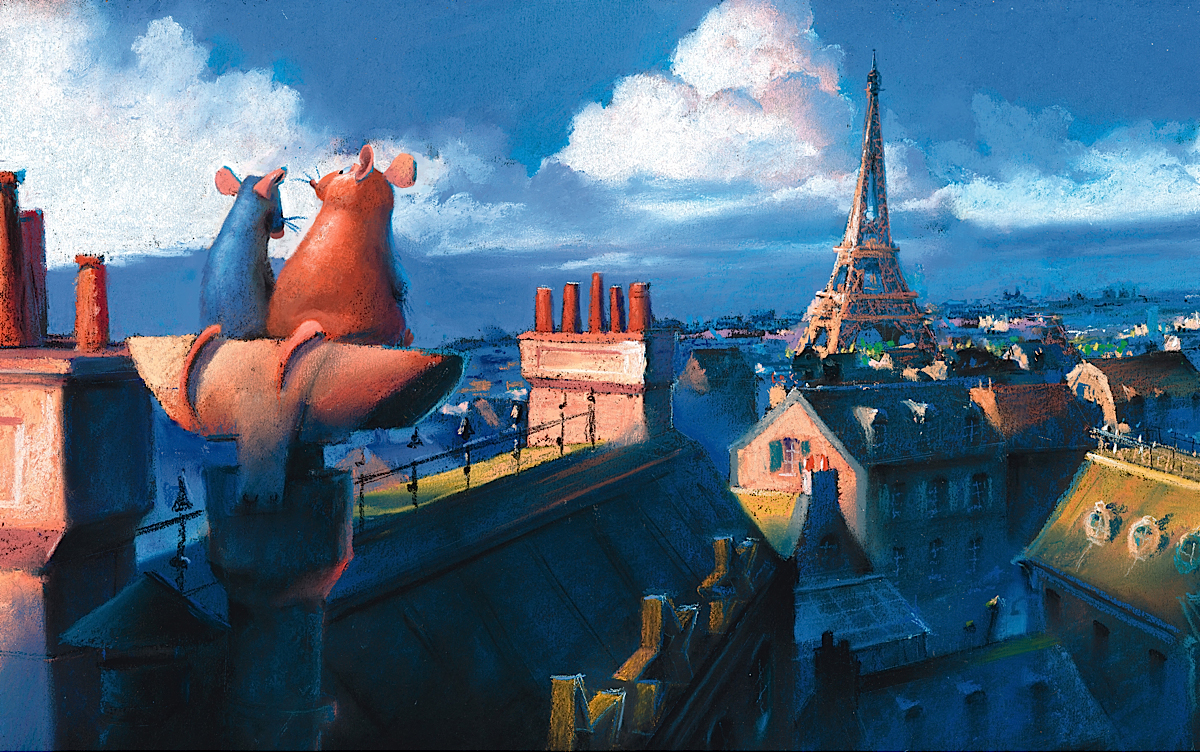

Ed Catmull, the president of Pixar, discusses his role in nurturing the early seeds of Pixar’s film ideas in his fantastic autobiography, Creativity Inc.[1] He cheerfully admits that, “early on, all of our movies suck. That’s a blunt assessment, I know, but I choose that phrasing because saying it in a softer way fails to convey how bad the first versions really are. Pixar films are not good at first, and our job is to make them so – to go from suck to not-suck.”[2]

Catmull recognises that creativity is a fragile thing, and has crafted an entire business model to protect it while it blossoms. Central to this model is Pixar’s famous storyboarding technique, which replaces the script as the traditional starting point of a film with a hand-drawn comic book of A5 pages stuck to a wall. As the film ideas develop and improve, individual pages or whole sequences are redrawn and replaced. Pixar went through 27,000 storyboard pages to produce A Bugs Life, 69,000 for Ratatouille and a whopping 98,000 for WALL-E.[3]

I like to think that the bits of paper are in fact physical manifestations of Pixar’s own conversational genius loci. And Catmull has gone to great lengths to protect them. Despite the forest-loads of paper, this early storyboarding phase is actually much, much cheaper than what comes next, when a couple of hundred animators convert the comic book into a feature film.

Thus storyboarding at Pixar has no time limit, only an imperative to lay down the bones of a perfect film. This is the period when a Pixar film goes from suck to not-suck, and where Pixar leverages maximum creative freedom for its storyboard teams by insulating them from the imperatives of economics.

Massing studies for a renovation to a Federation era house in Carlton North

We don’t have anything like the critical mass, creative freedom or economic autonomy of Pixar, but I think there’s a lesson in Catmull’s protective impulse.

Looking back at our growth, I realise that our inclusive, conversation-centred design approach developed intuitively. It was an organic response to an increasing project load and Erica’s and my decreasing ability to do the doing. Our larger team meant we were spending more time managing and administrating, and our roles on our projects were necessarily displaced from action to supervision.

Conversation has become the conduit through which we engage with our work.

Our projects now flow rhythmically between individual inquiry and collective reflection. When one of our staff sits down to solve a design problem, there’s no pressure for her to find the solution on her own. She’s far more likely to explore options whose purpose is to provoke subsequent discussion. This doesn’t erase the need for individual design genius, rather we use that genius to strike out in multiple directions that are each worthy of consideration, then use the genius of the group to pick the best alternative.

In other words, the individual experiments and the collective decides.

We’re now used to this new order, and we’ve discovered we enjoy our redefined relationship with our studio’s work. While conversation emerged organically as the genius loci of our design, we must work hard to sustain it. We seek it out and encourage our team to do likewise. We make time for it, at regular intervals, as needed, and serendipitously. Our discussions are not critiques, they’re collaborations. We talk and we listen, in equal measures. Conversation is more ephemeral than a storyboard, but it makes sense for our open, stretched-out, surprising design process.

I wonder how our conversation-centred design approach will evolve in the future. Will it still be useful for a team of 12? Or a team of 24? Or 240? Or will it transition again into something else entirely? My gut tells me that we’ve struck upon a resilient design philosophy. The people and media may change, but our commitment to experimentation and conversation is essentially scalable.

I believe we follow a similar creative process to Pixar, of taking a design idea from suck to not-suck. We experiment, we test, we pivot, we finesse. We do what Andrew Stanton, director of Finding Nemo says he does at Pixar, “be wrong as fast we can.”[4] We fail early and often so that our designs can improve and our best work can emerge.

Footnotes:

- If I weren’t an architect, I’d get a job at Pixar.

- Ed Catmull and Amy Wallace; Creativity Inc.: Overcoming the unseen forces that stand in the way of true inspiration; Random House; United States of America; 2009.

- Peter Sims; Pixar’s motto: going from suck to nonsuck; Fast Company; accessed May 2018.

- Ibid.

Images:

- Examples from Swedish artist Anastasia Savinova’s series, Genius loci.

- Experimental balsa models for Hood House.

- A massing exploration for another of our current projects, yet to be named.

- Early artwork from one of my favourite Pixar films, Ratatouille.