Blog | Heritage protection for Festival Hall

Festival Hall was built in 1955, replacing the 1913 West Melbourne Stadium that was destroyed that year by fire. The two buildings were the principal boxing and wrestling venues in Victoria until the late 1970s, and a principal live music venue until the 1980s.[1] Festival Hall’s decades-long association with the boxing community earned it the nickname, the House of Stoush, with some of boxing’s greatest names having fought there.[2]

Following a planning submission by the owners of the venue to partially demolish and develop it into apartments, Heritage Victoria has recommended it for heritage protection. Heritage Victoria’s report states that the hall satisfies two of the eight criteria for inclusion on the Victorian Heritage Register:

- Criterion A: Importance to the pattern of Victoria’s cultural history.

- Criterion G: Strong association with a particular community group for social or cultural reasons.[3]

The report elaborates on these points by stating that Festival Hall is:

- Historically and socially significant for its association with the boxing and wrestling community in Victoria.

- Historically and socially significant for its association with the live music community in Victoria.

Notably, the report states that criteria E and F, which deal with aesthetic, creative and technical achievement, are not satisfied. This would not be surprising to anyone who has visited the building, whose nondescript street frontage and rudimentary, hall-like interior are unremarkable.

The purpose of this article is not to analyse Heritage Victoria’s recommendation, but rebut an article written last week by Crikey columnist, Alan Davies. What follows is an expanded version of comments I left on Crikey, that have as yet not received a response.

Davies’ primary contention is that a building without aesthetic value is not an effective way of capturing important social values.[4] He claims that:

Preserving Festival Hall in perpetuity preserves the built form but tells us almost nothing about the social and cultural history of the place… We lazily preserve buildings like this simply because we can, not because they’re an effective way of conveying anything of substance about the happenings, incidents and proceedings that went on within or around them.

He goes on to argue that if Festival Hall is deemed worthy of heritage protection for its social value, then preservation of heritage features or adaptive reuse of the interior:

Tell us almost nothing about the activities that make it socially important… and convey little to future visitors about the excitement when Lionel Rose fought in the ring.

Davies’ article concludes with a clever suggestion to document Festival Hall’s history using soft tools like images, videos, and oral accounts, a proposal I support. However, his premise fundamentally misunderstands the way culture and architecture interact with one another, and the role architecture has in recording our past. I’d like to offer these four counter-arguments to Davies’ position:

Sirius Building by Tao Gofers, Sydney 1980

1. Aesthetics

The use of contemporary interpretations of aesthetics to judge the value of a building is an ill-considered bias that results in misplaced revisionism and dilution of heritage styles.

Aesthetic tastes change over time – what is unloved today often finds new life tomorrow. The Victorian and Federation era buildings that are so cherished today (and comprehensively protected via suburb-wide heritage overlays) were unloved in the 1960s and 70s. Many buildings of these eras were stripped of their period detailing: iron balustrades and lacework, stone scrolls and decorative capitals replaced with more utilitarian trims or simply scrapped. I see this regularly in our own residential renovations work, where older fragments of houses require extensive restoration to return them to their former glory.

Many Modernist and Brutalist era buildings are currently suffering the same fate as their Victorian and Federation counterparts did fifty years ago. There is no more prominent example of this than the Sirius building by Tao Gofers, pictured above. A recommendation for heritage protection two years ago by the NSW Heritage Council was rejected by the state government, with Finance Minister Dominic Perottet saying at the time that he looked forward to the “demise of the concrete eyesore and the promise of a new, less brutal building on the site.”[5] He later added that he thought Sirius to be “about as sexy as a carpark.”[6]

Perottet’s dismissal of the aesthetics of the Sirius building revealed a deep ignorance of both the Brutalist style and broader cultural value of Sirius. Observing the savvy but so far unsuccessful campaign to save what is unequivocally a remarkable building, I have often wondered whether the controversy surrounding it would all be a non-issue if Sirius happened to be elegantly Victorian, with red brick walls and delicate iron tracery.

Davies should be wary of using undesirable aesthetics as a justification for the demolition of Festival Hall, or any older building. I believe Heritage Victoria has the right approach with their eight criteria for inclusion on the Heritage Register: desirable aesthetics may be used to justify inclusion, but undesirable aesthetics may not be used to justify exclusion.

Murtoa Stick Shed, western Victoria 1941

2. Social value

Festival Hall is hardly the first building to be recommended for a heritage listing based primarily on its social or cultural value. Indeed, these qualities are captured by six of Heritage Victoria’s eight selection criteria.

This is not a coincidence. Individual works of architecture may possess powerful aesthetic or technical merit, but their true value lies in their relationships with the civilisations that created them. Architecture and culture are interdependent on one another, each informing and responding to the other. As Winston Churchill observed, “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.”

The preservation of buildings that express significant periods of our history is a necessary, though not always convenient, exercise. The Murtoa No. 1 Grain Store, more affectionately known as the Murtoa Stick Shed, is an excellent example of this. Built in 1941 as a wartime grain silo, it earned its position on the Victorian Heritage Register thanks to its “historical, architectural, technical and social significance to the State of Victoria.”[7]

The list of reasons for the Stick Shed’s inclusion on the Heritage Register is long, with cited ties to the development of the Victorian grain industry and effects of the Second World War. It is valued for its rustic construction methods, pivotal role in the invention of new grain-handling technologies, aesthetic qualities, and role in the early economics of the Wimmera farming region. In short, it’s a crackerjack of a building.

But it’s also inconveniently located, too far away from major cities to be sustained by tourism, too close to ongoing operations of the local grain industry to be readily accessible, and too fragile to be cheaply maintained.[8]

Davies argues that preserving Festival Hall will come at a high cost, both to its owners and to the city. I contend instead that to lose it due to the perceived inconveniences of its location and heritage fabric would be a tragedy. Like the Stick Shed, it exists thanks to the unique circumstances of a particular period in our history, and is worthy of living on as a record of the social and cultural values of its era.

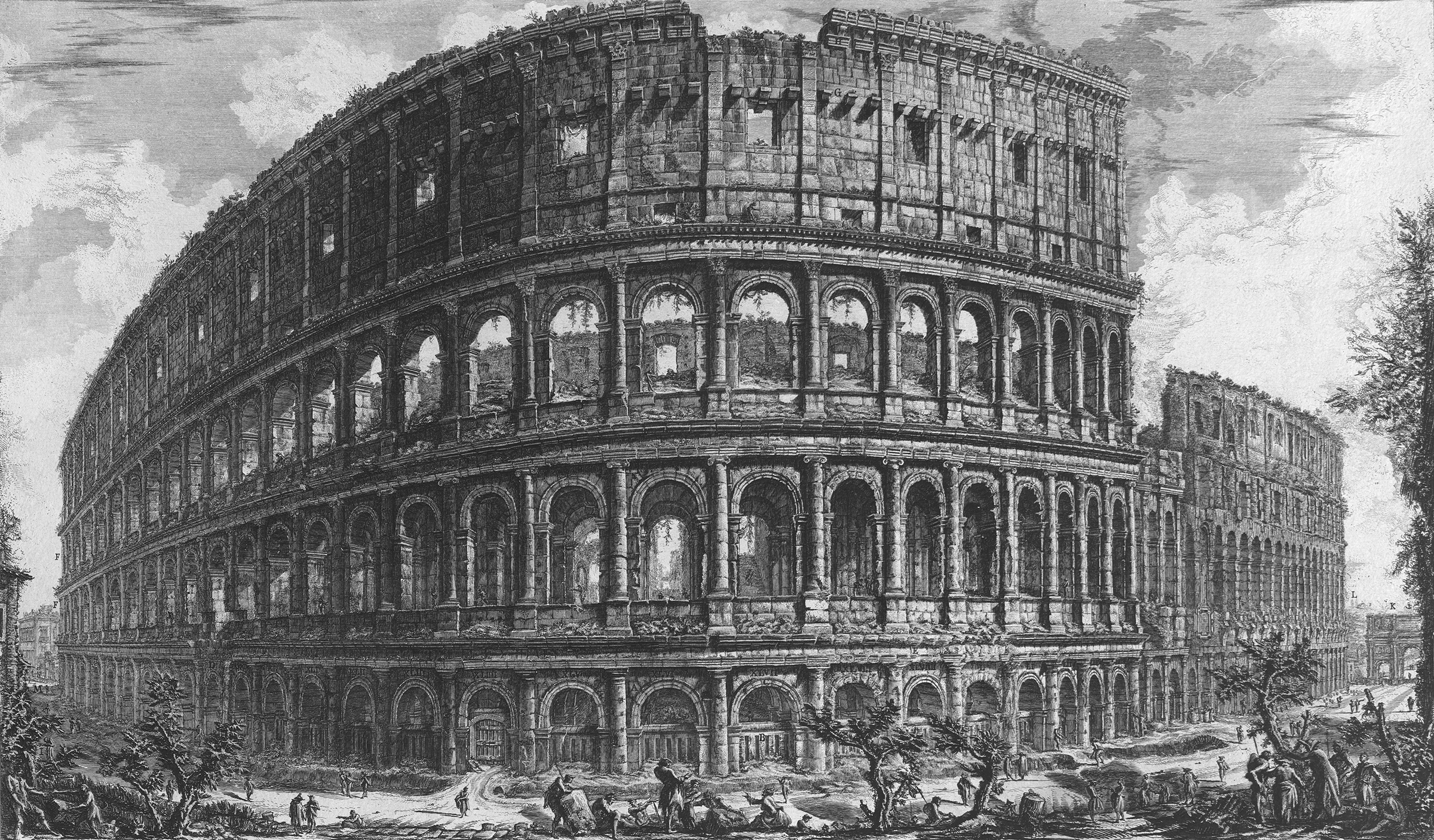

The Colosseum of Rome as depicted by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, 1757

3. Palimpsests

Something reused or altered but still bearing visible traces of its earlier form

Perhaps most erroneous of Davies’ claims is his assertion that, “buildings aren’t palimpsests, they don’t record what happened within them. They’re almost useless in that regard.”

A work of architecture is by definition a palimpsest. It remains new, unaltered and in pristine condition for a fraction of the time that it stands, soon succumbing to ageing from the elements, wearing from use, accidental damage and wilful modification. It accumulates visible traces of its use: layers of paint, worn floors, bricked-up windows and obsolete wires. At any given moment any time, it is a static image of its past lives and the people that inhabited it.

Architecture cannot offer re-enactments of the sights, sounds and smells of its inhabitation, at least not in the way that a film records an event. But it most certainly retains marks of their passing that can be detected and enjoyed. There is some simple logic in this: back in the heyday of Festival Hall, might it not have been possible to appreciate the excitement of a title fight or big concert the morning after? No music to be heard, but the echo of a large empty space and vacant seats recently filled. If this sixth sense of an event were discernible in the quiet moments before the next one, why wouldn’t they be discernible today?

Consider also the layers of meaning preserved in buildings like the Colosseum, Parthenon or Pyramids. The fabric of these ruined architectures are powerful evocations of the social, cultural and historical layers that once gave them life. Gladiatorial bloodbaths and the mummification of emperors could not be less relevant to contemporary civilisation, yet the stories of these buildings cling to them so profoundly that we flock to them in our millions each year.

There are other, less ancient versions of buildings-as-museums that find ways to reinvigorate the past. Harry Seidler’s Rose House, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater and Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye no longer serve the purposes for which they were built, but that doesn’t stop them from conveying the lives and actions of the families they once housed. Could Festival Hall not do the same?

The VCA School of Art by Kerstin Thompson Architects, Melbourne 2017

4. Adaptive reuse

And finally, Davies suggests that, “some likely forms of adaptive reuse, say an office or a library, might even be at odds with the former uses that made Festival Hall important.”

Aside from questioning Davies’ belief that an office or library are likely uses for Festival Hall at all, I’d like to offer the counter-observation that every heritage building contains the possibility for a sensitive and relevant adaptive reuse. The hushed tones of a library may be unsuited to the cavernous and once boisterous Festival Hall, but what about a recording studio, sports centre, marketplace, nightclub or coworking space?

I acknowledge that the golden years of boxing and wrestling are long behind us, and with the completion of Margaret Court Arena, that Festival Hall can no longer service the live music industry as it once did.[9] But there are many other large tranches of Melbourne’s built fabric currently under-utilised, heritage and otherwise. Initiatives like Renew Australia have found ways to regenerate vacant tenancies, by working with “communities and property owners to take otherwise empty shops, offices, commercial and public buildings and make them available to incubate short term use by artists, creative projects and community initiatives.”[10]

Additionally, there is a growing cohort of sensitively adapted heritage buildings around Melbourne demonstrating best practice regenerations of challenging sites.

At the forefront of this practice is Kerstin Thompson Architects, who recently converted the former Mounted Police Stables in Southbank into VCA’s new School of Art. Thompson is a master of adaptive reuse, and across all her projects exerts a highly considerate approach to reimagining old buildings as something new. At the School of Art, the rhythm of the old horse stalls has been preserved within new artist studios, the timber structure has been preserved and revealed, even original paint finishes have been stripped back and restored. There is much to love about this approach to adaptive reuse, and the careful balancing that must be done to both honour the history of a building and make it useful once again.

I agree with Davies that Festival Hall faces a difficult future. It is a complex building with a storied past. But dismissing the heritage value embodied in its fabric is short-sighted and will almost certainly result in an outcome poorer than it deserves. I suggest instead that the current owners of Festival Hall, descendants of the Wren family who built it sixty years ago, must find a way to balance its competing architectural, heritage, commercial and geographical needs, and find a way to both preserve its history and celebrate its future.

Footnotes:

- Steven Avery; Executive Director Recommendation to the Heritage Council; Heritage Victoria; May 2018.

- Venue history; Festival Hall; accessed May 2018.

- Steven Avery; Executive Director Recommendation to the Heritage Council; Heritage Victoria; May 2018.

- Alan Davies; Does Festival Hall warrant heritage protection?; Crikey; accessed May 2018.

- Sarah Keoghan; Legal challenge to save Sirius; The Daily Telegraph; September 2016.

- James Robertson; Sirius demolition one step closer as state government declines to grant heritage status; The Sydney Morning Herald; October 2017.

- Marmalake/Murtoa Grain Store, statement of significance; Victorian Heritage Database; accessed May 2018.

- A colleague of mine grew up in the Wimmera area, and reports that sheets of corrugated roof cladding used to rip free from the Stick Shed during high winds, occasionally landing in the playground of the nearby school (thankfully never injuring anyone).

- Festival Hall could be saved as Heritage Victoria recommends protection for Melbourne venue; ABC News; May 2018.

- About page; Renew Australia; accessed May 2018.

Image sources:

- Interior of Festival Hall circa 1957; Harold Paynting Collection; State Library of Victoria.

- Festival Hall in concert mode; source unknown.

- Sirius Building by Tao Gofers; photo by Katherine Lu.

- Murtoa Stick Shed; source unknown.

- The Colosseum by Giovanni Battista Piranesi; 1757

- VCA School of Art by Kerstin Thompson Architects; photo by John Gollings.